I have always been a fan of static site generators. Back in my college days, when I was running college projects on free AWS credits courtesy of the GitHub Student Pack and a few hackathon credits, I had to minimise expenditure in every possible way. So when it came to my own website, the cheapest possible way to host it was to just use some cheap shared hosting service. This costed somewhere around 10-15USD a year and it was something I could barely manage to afford. When GitHub Pages entered, things became easier. Instead of uploading a zip on CPanel and then extracting it, I had to just check-in the generated files into the gh-pages branches and the hosting was taken care of.

However, all this dependeded on one crucial requirement - no dynamic/moving parts. You had to give GH Pages plain HTML, CSS and JS files(if not using Jekyll) and it would be served. Compare this to something like WordPress that has to do a lot more stuff(like quering databases) to display a page. Clearly, speed is something that static sites shine in. Even security wise, static sites should be better off because there is an absolutely minimal surface area for threats.

So many static site generators!

When I started off with the website(way back in 2015), my initial choice was Jekyll. GitHub Pages supported it out of the box and the Liquid templating language is one of the best of its kind. However, I didn't settle on it as GH Pages didn't allow plugins and this was a deal breaker to me. The alternative was checking in the build folder in the repo. The other options available at that time were Pelican and Flask(with Frozen-Flask) and I settled with Flask for the following reasons.

- I am extremely comfortable with Python. In fact, that language and community is why I got into programming in the first place. I could easily write custom plugins if I wanted to.

- I could run my college apps and my personal site with the same codebase thanks to Flask's insanely simple

routedecorator. - Flask's templating language Jinja2 was very similar to Liquid.

I still had to check-in the build folder but I was okay with this as the pros were much better. This served my purpose well for over three years.

Why write a new one?

Towards the middle of 2018, I was looking at ways to optimise my site's performance. I wanted to minify the ES6 code that I had written recently and do stuff like prefetching. Pretty straightforward, right? Turns out, no. All the plugins that I could find for Flask were outdated. No support for ES6+ code, inlining JS and CSS didn't work if there was a defer or async attribute and numerous other weird shortcomings came to light. While I would have loved to contribute to the plugins and continue using Flask, I did not have that many free cycles to spare and the site was on a backburner for quite some time. I had also stopped running the college projects about a year and a half back and all the pros I had back then were slowly getting away. I considered moving to Hugo(which is insanely fast when it comes to generating builds) but was put off because Hugo has several conventions(like _index.md) that I am not quite comfortable with. While I fully agree that Hugo is extremely powerful, I didn't need something that heavy and complicated.

Gatsby was another choice that did everything I wanted a static site generator to do but I would have had to basically rewrite the entire website from scratch(Jinja2 to JSX, write GraphQL queries, etc.). This is when I had the weird idea of writing a static site generator that would fit all my needs. If I had to rewrite everything from scratch to switch to Gatsby, I might as well write a static site generator itself. I would have one more opportunity to learn! I had written several build tools at work and thought it would be nice to do spend a few minutes everyday building a hobby project. This is how lego was born.

Goals that I set for the project

I decided to create a list of initial expectations that I wanted lego to be capable of.

- Support Liquid templates - Even though the site was using Jinja2 templates, I decided to go for Liquid as it has a better npm ecosystem and is very similar as well in terms of syntax.

- Support markdown posts

- A capable task runner - It should be capable of running tasks in parallel. For example, minifying CSS and JS can take place in parallel resulting in reduced build timings.

- Asset optimisation - Minification and uglification of JS and CSS files, revisioning them, inlining required assets, minifying output HTML, optimising images, etc.

- Sitemap generation

- A decent enough development server with live reload - I absolutely love tools that enable real time feedback. This is critical especially when working on websites because you can see your changes then and there and it helps in maintaining your flow of thoughts.

- A simple directory structure - I always admired the simplicity of the Jekyll project structure and wanted something similar to that.

- Extract tags from posts' metadata and create relevant pages - Example,

site.com/tags/javascript/should have a list of all posts taggedjavascript.

Update: I have now added the following features as well

- RSS Feed generation

- Build time code highlighting - This uses highlight.js. A CSS file can be included to style the generated markup as needed. There are plenty of themes available for hightlight.js.

- Caching - This was always planned but I actually got around to doing it only for v2 of lego. lego is now fast ⚡. Initial benchmarks suggest that lego is as fast as Jekyll while still doing additional stuff like HTML minification out of the box. At the time of writing this, my own site, which has about 80 pages in the output and about 40MB of static files takes 2 seconds to start a development server. Rebuilds take a couple hundred milliseconds. A production build that does all the above optimisations takes about 35 seconds without a cache and less than 10 seconds with an existing cache.

Update: lego is now 8.7x faster than Jekyll! My site starts up in <600ms and production builds take 20 seconds.

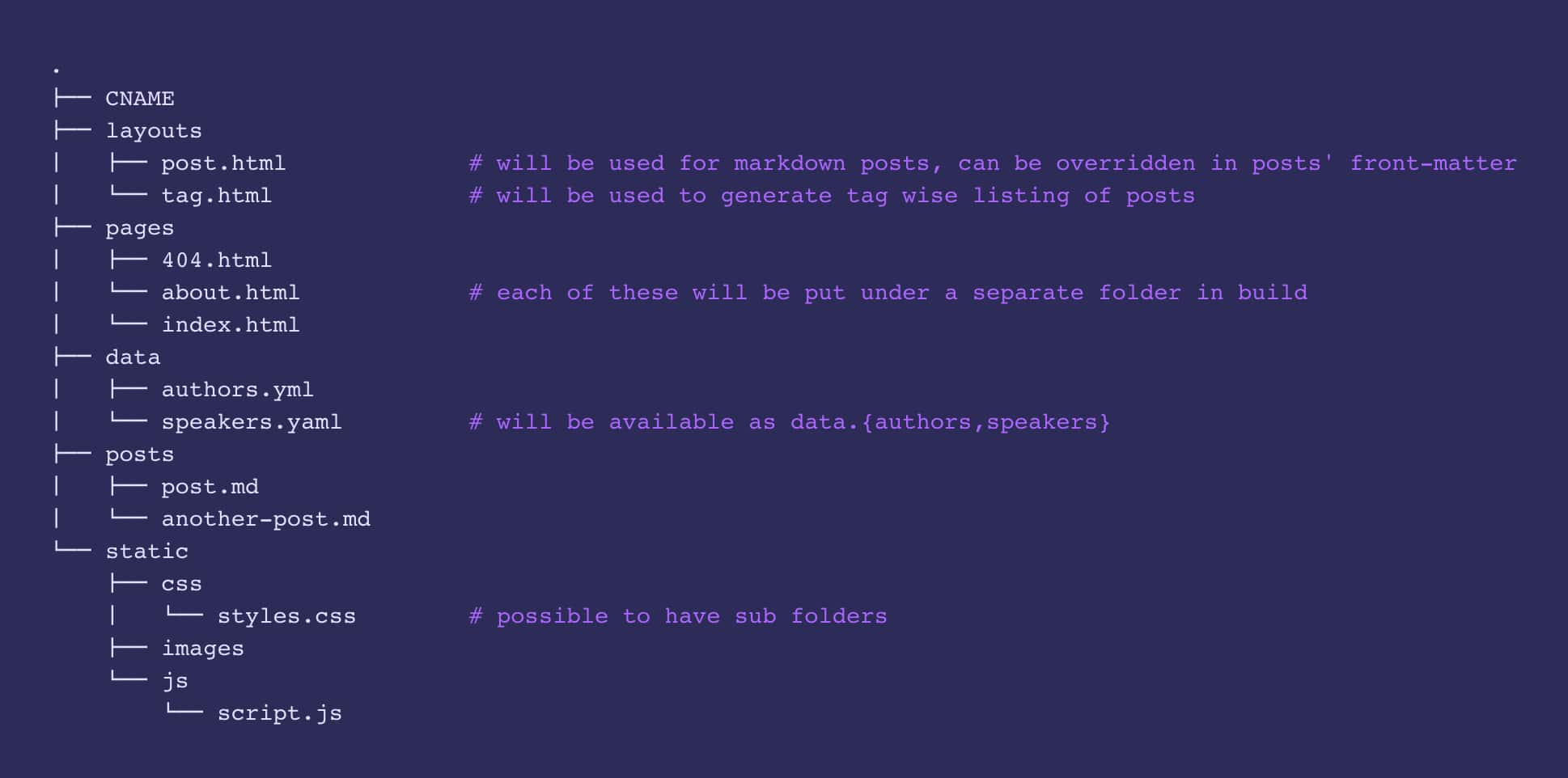

Project directory structure

This is the directory structure that I eventually settled on.

While each file in posts will be generated in build/post/index.html by default, it is possible to override this by providing a url field in the file's front-matter. I also like to have my posts organised by topic in the repo but want them to be built to the same path so lego.js lets to provide a flatUrls option at the project level that lets to skip directory names in the generated URLs.

For example,

.

└── posts

├── travel

│ └── nepal.md

└── i-love-js.md

The URL of nepal.md will be site.com/nepal if this option is true. By default, the URL of this post would be site.com/travel/nepal. This option will be overridden if the post's front-matter has a url field.

Creating a simple yet capable task runner

At the core of lego is a task runner that does various operations on each of these directories. Some of the critical tasks are:

- Generating posts from markdown files in the posts directory(using markdown parser).

- Creating landing pages from the pages directory(using Liquid parser).

- Create a list of posts for a specific tag.

- Copying assets, minifying and uglifying them.

- Revisioning assets.

- Extracting and inlining critical CSS.

- Optimising images.

- Generating a sitemap.

While some of these can be run in parallel, there is a specific sequence to be followed. For example, extracting and inlining critical CSS with critical and optimising images can run in parallel but it can happen only after the assets themselves have been uglified and revisioned. Otherwise, lego will be trying to inline files(say, script.js) and the asset revision script would have just changed it to script-123.js and this will result in an error.

So what is needed is an API similar to Gulp's gulp.series and gulp.parallel. Here is some code that demonstrates how this can be implemented:

There is a task folder inside lego that contains these tasks. The name of the task used in the code is the same as that of the file name.

const tasks = {};

const tasks = fs.readdirSync('./tasks', { encoding: 'utf8' });

// filter hidden files

// ...

tasks.forEach((task) => {

tasks[path.parse(task).name] = require(`${pathToTasks}/${task}`);

});

The task runner can now call tasks['revisionAssets']() and that task will be run. Each of these tasks return a promise and can take any number of arguments.

const build = [

'revisionAssets',

[

'optimiseImages',

'extractCritical',

'inlineAssets',

'generateSiteMap'

]

];

The task runner iterates over each element of this array and if it is a string, waits till the task is resolved. If it is an array, it calls each of them and pushes all the returned promises into an array. Using Promise.all, we can determine if the parallel tasks have all executed and then move on to the next task.

if (!Array.isArray(task)) {

task = [task];

}

for (const taskUnit of task) {

if (Array.isArray(taskUnit)) {

let taskUnitPromises = [];

for (const parallelTask of taskUnit) {

taskUnitPromises.push(tasks[parallelTask](options));

}

await Promise.all(taskUnitPromises);

} else {

await tasks[taskUnit](options);

}

}

Fast live reload capability

This is probably one of the most critical part of lego. While lego takes roughly 3-4 seconds to start a development server, rebuilds are insanely fast and instantaneous. This can be achieved only if you rebuild only the files that have changed. To do this, lego has an in-memory representation of all the posts in the project and when a post has changed, only that post is modified and this is passed to all places that are dependent on that post.

For example, consider the following function that generates html from markdown files.

function generateHtmlFromMd(changedPath) {

let files;

files = changedPath ? [changedPath] : readFilesInDir('posts', '.md')

for (file in files) {

// render md as html

// ...

// write to build

}

}

How does lego determine which files have changed? By using a watcher like chokidar.

let postsWatcher = chokidar.watch(

[`posts/**/*md`, `posts/**/*html`],

watchOptions

);

postsWatcher.on('all', async(event, path) => {

// handle post change

// ...

// path will be the changed file's name

});

Responsive image generation

markdown-it supports custom containers. Using that, I wrote a plugin that would generate images for various resolutions and insert a <picture> tag with appropriate <source> tags.

::: lego-image

src="static/images/hello.png"

res="1080,500,320"

alt="alternate text"

class="img-responsive center-block" :::

Putting together the rest of the pieces

I now wanted to build features into lego that would optimise the site's performance. This was fairly straightforward. I just had to figure out what npm packages to use and add them as tasks. I use the following plugins(most of these can be configured by passing options to lego.js):

- terser - JS uglification and minification

- cssnano - For CSS minification

- postcss-preset-env - Transpiling CSS

- html-minifier - The defacto html minifier out there. Had to disable built-in minification of JS and CSS as terser and cssnano had much more support for the latest features and performed better.

- imagemin and associated plugins for optimising images

- critical - To extract and inline critical CSS

- rev-hash - To generate an md5 checksum of file contents. lego then appends this hash to all file names.

I decided to skip transpiling JS using babel for older browsers. This was mainly because the JS in this site is very minimal and transpiling them would greatly increase their size. Implementing this was very easy however, and if somebody other than me starts to use lego for their website, I will happily add that piece of code again.

For generating sitemaps, I hard-forked tmcw's sitemap-static into @astronomersiva/sitemap-static to align it with the Gulp equivalent. Provided with a folder containing html files, this will generate a sitemap and place it in the build folder.

Was it worth it?

This site currently runs on lego. Was it really worth all the effort? To me frankly, I had a lot of fun writing the static site generator. I learnt a lot of stuff, experimented a ton and saw some really weird stuff. I had concerns if I would be spending too much time writing this instead of blog posts for my site but looking back, I think it was totally worth it.

I learnt that it is never a good idea to reassign function parameters. There is an ESLint rule for this that I recommend enabling in all ypur projects. This one bit me badly because one of my dependencies was manipulating the list of posts and I always ended up with a few missing posts. Took me hours to figure out why this was happening.

During the initial days, lego would take about 5-6 seconds to start a development server. I profiled it with flamegraphs and time-require and found out that about 2-3 seconds were spent just requiring postcss and its plugins. I then moved the

requirestatements such that they only ran for production builds and I had an easy improvement. Whileimportstatements are hoisted,requirestatements are executed in place. Sincerequirestatements are synchronous, this might be bad for most cases. However, for CLI tools like static site generators, this can actually turn out to be an easy win.I learnt of v8-compile-cache. It attaches the require hook to use V8's code cache to speed up instantiation time. I had about 5% improvement in speed thanks to this.

Here is a gif that demonstrates the improvement of lego's performance to start a development server over time:

Can I contribute?

If any of you reading this would like to contribute, please go ahead! I would love to see more people use this. While lego has largely been driven by my own needs, I am always open to see new features getting added to it.

Two things that I would like to see improved in lego are logging and tests. There is a decent logger right now but that can be greatly improved. There are no tests other than ESLint as of now and I use my own site to test changes by checking the build folder between different versions to make sure nothing is broken.